On a street of the city of Constantinople, in many ways the foremost metropolis of the world of its time, two middle-aged men walked with long strides. Their sumptuous clothing, made of rich textiles, was of the highest quality. As they strode, an impassioned conversation developed between them:

— No, no. Jesus was not God and Man; the divinity covered Him like this tunic covers you. I can almost hear the words of the last sermon: “Jesus is a God for me, seeing as He encompasses God. I adore the vase because of its content, the garment for what it covers.”

— I am not so sure of that.

– the other pensively replied – there are numerous passages from Sacred Scripture that conflict with your affirmation. Have you never read in the Gospel: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1:14)?

— Yet, if Jesus were truly the Word, how do you explain that He died on the Cross? It is clear: it was only Christ’s humanity that suffered the Passion.

The discussion was becoming more complex. Both felt as if they were “walking on eggs”… If it were only a man who died on the Cross, infinite

merit could not be attributed to His sacrifice, and this would imply denial of the Redemption. What would remain of the Catholic Faith?

These and other question filled the thoughts of the two men when, finally, the more resolute ventured:

— I, too, was reticent at first… But knowing that the main defender of this doctrine is none other than our illustrious Bishop, I adhered to it wholeheartedly.

The dialogue had to be interrupted: they had arrived at church. Many had already gathered in the main nave and people were vying for the last available seats in the side aisles. What was about to happen?

Nestorius denies the Divine Maternity

In that early time of Christianity, Nestorius was known for the eloquence that flowed from his lips. Many considered him a “second Chrysostom”… In Antioch he had distinguished himself as a monk and, elected Bishop of Constantinople in 428, “in all of his actions he had always appeared as a profoundly religious man, a reformer of the people and the clergy, and by his ascetic life and with the passion of his oratory had enkindled and captivated all those who heard him.”1

Undoubtedly, many Catholics considered him to be a holy man, entirely dedicated to the Church and concerned with the faithful. It was easy to feel veneration for such a pious and ascetic prelate. And here was a crowd gathered to listen to a disciple of Nestorius, a priest of his confidence.

The preaching began. History has not passed down his words. The only thing that is known is that he spoke about the Blessed Virgin, for whom his listeners had sincere love and devotion.

He said that, despite her grandeur and sanctity, Mary was not the Mother of God, Theotokos. How could a creature engender the Creator? She was the Mother of the man Jesus, and nothing more… A noisy murmur ran through the crowd. The faithful burned with indignation, some wept with outrage at seeing the most perfect creature so unscrupulously degraded. Many left the church, awaiting further explanations.

However, far from Constantinople, there was someone who was not satisfied with a fleeting and fruitless reaction. And taking upon himself the defence of the cause of the Incarnation of the Word and the Divine Motherhood, he entered the fight against the heresy.

The upright conscience of the Patriarch Cyril

Where was he born? Who were his parents? What formation had he received? It is not possible to respond to any of these questions with certainty. St. Cyril of Alexandria enters history as the fruit of an ardent love for Jesus Christ and His Virginal Mother.

Of his blood origins little is known, other than that he was the nephew of the Patriarch of Alexandria. In his writings a thorough understanding of the pagan classics emerges, proving that he was well educated. Nevertheless, not these, but the ancient Fathers of the Church were the foundation of this thought.

His works are not of a poetic or artistic style, but are characterized by the clarity of the ideas and their polemical tone. The circumstances demanded this!

With the death of his uncle, Cyril ascended to the episcopal See on October 17 in 412. A few years later, the holy Patriarch received news of the new doctrine defended and promulgated by Nestorius, which was spreading among the monks of Egypt. Due to his ardent and combative character, he decided to take vigorous action immediately.

His alacrity in defending the Faith merited this tribute from Pius XI, many centuries later: “Among the opponents of the Nestorian heresy, some of whom were found in the Eastern Empire’s capital city, the first place was surely occupied by that most holy man, the paladin of Catholic integrity, Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria.”2

From the outset, St. Cyril sets an admirable example of submission and respect. Upon encountering the doctrine of Nestorius, could he not have issued an opinion based on his knowledge and studies, and employing his patriarchal jurisdiction? He proceeded otherwise. Such was the uprightness of his conscience that he refused to “pass sentence in such a grave matter, until he had first sought the judgement of the Apostolic See and had ascertained its

“Satan is on the verge of overturning everything”

At the time, Celestine I occupied the Chair of Peter, and to him Cyril addressed a reverent missive, having recourse to the ancient custom of the churches, which, in his words, “obliges us to communicate events of this nature to Your Holiness.”4

For this reason, he adds, “I am obliged to write you, to warn you that satan is on the verge of overturning everything. Enraged against the churches of God, he seeks to disturb the peace of the faithful everywhere. This nefarious beast, who takes pleasure in impiousness, will never rest. Until the present, I have maintained complete silence and have written absolutely nothing to Your Holiness nor to your brothers in the priesthood regarding him who presently governs the Church of Constantinople, for I know perfectly well that precipitation in this matter may be pernicious. Nevertheless, as the evil is now ready to attain its apogee, it is absolutely necessary to break the silence and to tell you everything that has happened.”5

Now, this was not the first time that the Pope had received news of the upheaval that devastated the churches of the East. Seething with pride, Nestorius would brook neither criticism nor opposition. He demonstrated such assurance of his superiority that he did not even bother to respond to the theological objections that were made.

He accused some monks who defended the Faith of rebelling against the public order, denouncing themto the government and managing to have them imprisoned. Finally, he even dared an attempt at proselytizing the Roman Pontiff, to whom he sent a letter, in 429, “offering him, among other things, a large collection of his homilies.”6

With his discernment and wisdom, the Pope immediately detected the error hidden under the guise of sound doctrine, as well as the vile intentions of their propagator. Accordingly, he sent the writings of Nestorius to the gifted abbot of St. Victor, in Marseille, so that he could offer his opinion.

The reply from the religious reached Celestine I together with the letter of St. Cyril. Taking this as a providential sign, the Pope designated the latter as papal legate and judge on this very important question, and wrote to Nestorius himself, ordering him to submit to the decisions of the holy Patriarch in everything.

There should be no doubt about acting when the Faith is threatened

The great days of Alexandria were over, in both the civil and spiritual sphere. The time of the great polemics that had enlivened the city during the life of Athanasius was long past. It was now a quiet and peaceful place, though still illuminated with yearnings for that golden age.

How could Cyril fail to appreciate the tranquility of his surroundings? It would have been much more agreeable for the Bishop of Alexandria to keep silent and continue this tranquil life, free of risk. Furthermore,

the evil was not centered in his territory… But could he remain silent, without blame, “when the Faith, being corrupted by many, is at grave risk?” 7

There was only one answer, registered in his own hand as follows: “I love peace; nothing displeases me more than quarrels and disputes. I love everyone and if I could cure a brother by surrendering all my goods and possessions, I would be ready to do so joyfully, for harmony is what I most esteem… But the Faith is threatened and a scandal awaits all the churches of the Roman Empire… The sacred doctrine is entrusted to us… How can we remedy these evils?… I am ready to calmly endure every torture, humiliation and offence, so that the Faith suffer no harm.”8

Even so, the prospect of initiating a bitter polemic with a brother in the Episcopate wounded his soul: “I am filled with affection for Bishop Nestorius, who no one loves more than I… […] But when the Faith is threatened, one should not hesitate to sacrifice one’s own life.”9

Celestine I convokes the Council of Ephesus.

With the authority invested in him by the Supreme Pontiff, he convoked a synod in Alexandria, at which were composed the famous twelve anathemas that would later bear his name. In them, the holy and peaceful Patriarch warns, rebukes and condemns!

The twelve anathemas were sent to Nestorius with the express order to give his consent to them. This was a terrible affront to the heresiarch’s pride, accustomed as he was to imposing his will in everything. He therefore endeavoured to gain the good graces of Emperor Theodosius II, who, being of a pacifying nature, asked the Pope to convoke a council.

Had not Celestine I already responded to Nestorius, condemning his doctrine? What was left to decide? However, the situation was sensitive and the Pope acceded to the emperor’s wishes: the council would be held in Ephesus, in 431. The Bishops Arcadius and Projectus, together with the priest Philip, were appointed papal legates. Cyril received the instruction to hear Nestorius although, his doctrine being known, there was no room for doubt regarding his condemnation.

Nestorius and his followers were the first to arrive; Cyril appeared soon after, accompanied by fifty Egyptian prelates. Little by little, the others arrived. Nevertheless, the papal legates did not appear. Thus, the Patriarch of Alexandria opened the council!

The Church proclaims the dogma of the Divine Motherhood

Some historians dispute the validity of this first session. However, the famous Fr. Bernardine Llorca, SJ, defends that “St. Cyril undoubtedly had the faculty to begin the sessions of the council and, consequently, the

decisions taken by him were entirely valid.”10

It remains to be discussed if it would have been more prudent to await the arrival of the pontifical legates and the Patriarch of Antioch. However, to prolong the wait would have brought even greater harm to the Holy Church, given the opposition demonstrated by the emperor to the Pope’s designs.

With the sessions underway, “the correspondence exchanged between St. Cyril and Nestorius was read, the sentence given by the Pope at the Synod in Rome, a long series of documents from the Fathers of the Church arguing in its favour and, finally, the sentence pronounced against Nestorius and his doctrine, after which he was solemnly deposed.”11

The people enthusiastically flocked to the church where the great assembly was being held and “they accompanied the departure of the conciliar fathers, acclaiming them throughout the city.”12 The divinity of Christ, the

Word Incarnate, God made Man, had been officially declared. This opened the way for the proclamation of the dogma of the Divine Motherhood of Mary!

The defender of orthodoxy is accused of heresy

All the vicissitudes suffered by St. Cyril after the council would be much too long to narrate here. After having made use of him to consummate the triumph of the true doctrine, Providence wished to subject him to a harsh trial; learned and influential persons within the Church accused him of heresy!

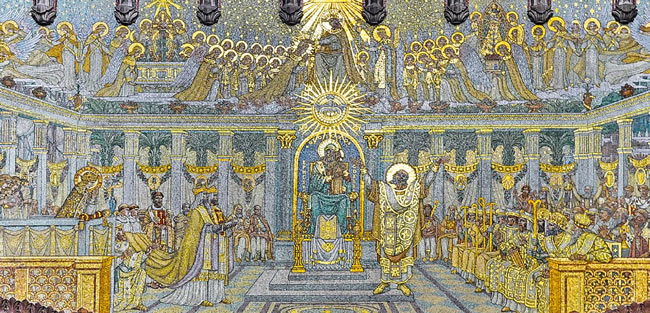

The Council of Ephesus – Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourviére, Lyon (France)

How could the intrepid defender of orthodoxy have deviated from the Faith? Nevertheless, the Patriarch John of Antioch and the priest Theodoret of Cyrus affirmed there were signs of this…

The people enthusiastically flocked to the church where the great assembly was being held; this opened the way for the proclamation of the dogma of the Divine Motherhood of Mary!

In those times, in which theological knowledge and language were still in their early days, Cyril used certain formulations that could be interpreted as a defence of Monophysitism. Now, could it be that he was, in reality, an adherent of this opposite heresy, which advocated just one nature in Christ, a fusion of the divine and human?

Throughout his whole life, the Patriarch of Alexandria had shown himself to be carved from the same “block” as the Saints. Being the official representative of the Pope, it was easy for him to rightfully impose his criteria. However, he preferred to bow before the demands of his accusers, giving them all the explanations necessary to convince them of the orthodoxy of his affirmations. And when John of Antioch demanded that he remove certain expressions from his writings that might serve as a pretext for the enemies of the Faith, he gladly consented to do so.

The result of this sensitive polemic was the Edict of Union of 433, which, according to the previously cited Fr. Bernardine Llorca, “should be considered an indispensable compliment to the Council of Ephesus.”13 With this document, St. Cyril and the Patriarch John declared their desired communion, to which Theodoret later adhered.

This exemplary demonstration of humility from the holy Patriarch is one of the greatest proofs of the heights that he attained in the firmament of the Church. The Theologian of the Incarnation, the promulgator of the first of the Marian dogmas, and the paladin of the true Faith did not hesitate to seal the orthodoxy of his doctrine with his meekness and modesty.

1 LLORCA, SJ, Bernardine. Historia de la Iglesia Católica. Edad Antigua. 5.ed. Madrid:BAC, 1976, v.I, p.523.

2 PIUS XI. Lux veritatis, 25/12/1931.

3 Idem, ibidem.

4 ST. CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA. Epistola XI, apud DU MANOIR DE JUAYE, SJ, Hubert. Dogme et spiritualité chez Saint Cyrille d’Alexandrie. Paris: Vrin, 1944, p.31.

5 Idem, ibidem.

6 LLORCA, op. cit., p.525.

7 ST. CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA, op. cit., p.31.

8 ST. CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA. Epistola IX, apud DU MANOIR DE JUAYE, op. cit., p.35.

9 Idem, ibidem.

10 LLORCA, op. cit., p.529.

11 Idem, ibidem.

12 Idem, ibidem.

13 Idem, p.532.